Commercial loans are still quite hard to close these days. Here are ten practical tips that will help you qualify for a commercial loan:

Commercial loans are still quite hard to close these days. Here are ten practical tips that will help you qualify for a commercial loan:

- Instead of calling random commercial mortgage companies for your commercial real estate loan, focus your phone calls on commercial banks. Commercial banks make the most number of commercial loans these days. You can also save yourself countless phone calls by simply using C-Loans.com.

- Don't forget about credit unions. Credit unions, who historically never made commercial loans, have come out of nowhere to seize 5% of the commercial real estate lending market over the past two years.

- Use local lenders. Many commercial mortgage borrowers are under the mistaken belief that some mystical nationwide commercial lender offers lower rates than a local bank. This is simply untrue. You'll get your best commercial mortgage deal from a commercial lender located close to the subject property.

- You can find all of the banks and credit unions located close to your commercial property by merely plotting your property on maps.google.com. In the left column you'll see a photo. Click the hyperplink underneath the photo that says, "Search Nearby." Simply enter "banks" and hit return.

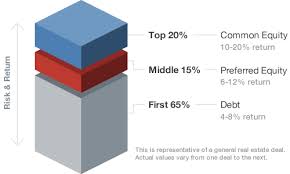

- If you are trying to buy a commercial property, and you don't qualify for an SBA loan, you are about to discover that you have a problem. Most commercial banks will not make conventional (non-SBA) commercial mortgage loans in excess of 58% to 63% loan-to-value these days. This means that you have to put 37% to 42% down. Yikes! Who has that kind of money?

- You can solve this problem by using preferred equity investments from Blackburne & Sons.

- What if you have a $2 million balloon payment coming due on your commercial property, but the bank will only lend you $1.6 million? A $400,000 preferred equity loan from Blackburne & Sons might save your property. (Technically our $400,000 is not a loan but rather an equity investment; but its easier to think of it as a tiny mezzanine loan.)

- If you are in the commercial loan business, make sure you are building your list of referral contacts every day. I am a huge fan of list advertising. The cold weather has greatly slowed commercial loan demand this winter, but my own commercial mortgage company, Blackburne & Sons, was able to respond by doubling the number of email newsletters and fax newsletters that we send out every day. I am pleased to report that we did this, and my loan officers are once again deliciously buried with commercial loans.

- Don't give up on your commercial mortgage newsletters too soon. Your first five newsletters may not generate a single lead, but if you send out a fun, folksy, unprofessional commercial loan newsletter every 10 to 21 days religiously, your sixth newsletter will be a hit. I promise you! Why? It takes a while for The Newsletter Effect to kick in, but once it does, it is a powerful force. This is what happened to my own son, Tom. "Dad, these stupid newsletters aren't working. No one is calling." Then his sixth newsletter hit. Bam! His phone have been ringing like crazy ever since. I've got to tell you, it felt good to be vindicated in front of my own son. Need more help with your commercial mortgage marketing?

- You could easily be closing three times more commercial loans than you are today, but you keep making 67 different mistakes. I recently finished my training masterpiece, my Commercial Mortgage Broker Practice Course. The course contains 67 different, very practical lessons on commercial mortgage brokerage, including the very first thing to say to a commercial lender when you call him to run a deal by him and including the single most important lesson in all of commercial real estate finance. It's a five-hour audio course, designed to be listened to in your car on long drives. Ideally you should listen to it at least five times, but if you listen to it just three times, I promise you will triple your income as a commercial mortgage broker. "But George, I'm as poor as a church mouse right now. I can't afford $199." No problemo. Simply submit two commercial loans using C-Loans.com and earn $100 Blackburne Bucks for each submission. Then you can buy this amazing course without it costing you one penny out of pocket. Folks, it will change your life!

If you are a conventional buyer of commercial real estate, or if you are a commercial broker, this article is VERY important to you. The reason is because you are about to discover a BIG problem with your next commercial real estate loan.

If you are a conventional buyer of commercial real estate, or if you are a commercial broker, this article is VERY important to you. The reason is because you are about to discover a BIG problem with your next commercial real estate loan.

Nobody is applying for commercial loans right now. In my 33 years in the commercial loan business, I have seldom seen the commercial real estate finance industry so dead.

Nobody is applying for commercial loans right now. In my 33 years in the commercial loan business, I have seldom seen the commercial real estate finance industry so dead.

Obtaining a commercial real estate loan these days is VERY expensive. There are lender points. There are broker points. There is an appraisal of the property by a General Certified Appraiser or an MAI appraiser. There is the toxic report. There is the survey and the title commitment. Some commercial lenders want an engineering report, and some even require a maximum probable loss (earthquake) report. There are also closing costs, like attorney's fees, escrow costs, and title insurance. The last thing a commercial property owner wants to do is to pay these fees and costs all over again when he gets a new commercial loan.

Obtaining a commercial real estate loan these days is VERY expensive. There are lender points. There are broker points. There is an appraisal of the property by a General Certified Appraiser or an MAI appraiser. There is the toxic report. There is the survey and the title commitment. Some commercial lenders want an engineering report, and some even require a maximum probable loss (earthquake) report. There are also closing costs, like attorney's fees, escrow costs, and title insurance. The last thing a commercial property owner wants to do is to pay these fees and costs all over again when he gets a new commercial loan.

Incoming commercial loan leads were outright crumby for

Incoming commercial loan leads were outright crumby for

Because we have been in the commercial mortgage loan business for over 33 years, and because we own CommercialMortgage.com, Blackburne & Sons just got approved to originate and sell apartment loans to this investor. These apartment loans actually close in our name, but they are quickly sold off to our institutional investor. The vetting process took over six months to complete, but we are now one of only six mortgage banking firms in the entire country allowed to originate loans for this investor in our own name.

Because we have been in the commercial mortgage loan business for over 33 years, and because we own CommercialMortgage.com, Blackburne & Sons just got approved to originate and sell apartment loans to this investor. These apartment loans actually close in our name, but they are quickly sold off to our institutional investor. The vetting process took over six months to complete, but we are now one of only six mortgage banking firms in the entire country allowed to originate loans for this investor in our own name. This may be one of my most important commercial loans blog articles ever because I explain almost a dozen new commercial finance

This may be one of my most important commercial loans blog articles ever because I explain almost a dozen new commercial finance

We will start our six-part journey in the 1960's, at a time when the United States was still on the gold standard, and inflation was close to zero. Back then there was no organized secondary market for commercial loans. If a bank or life insurance company ("life company") made a commercial loan, it was a

We will start our six-part journey in the 1960's, at a time when the United States was still on the gold standard, and inflation was close to zero. Back then there was no organized secondary market for commercial loans. If a bank or life insurance company ("life company") made a commercial loan, it was a

There is some logic in this position. Many commercial property investors trade up to a more expensive commercial property, one with even more depreciation, every five to seven years. Therefore it makes little sense to spend a lot money to obtain a long-term commercial loan, if that commercial loan is simply going to be paid off quickly.

There is some logic in this position. Many commercial property investors trade up to a more expensive commercial property, one with even more depreciation, every five to seven years. Therefore it makes little sense to spend a lot money to obtain a long-term commercial loan, if that commercial loan is simply going to be paid off quickly.